In my previous post I briefly explored some of the changes in our western culture, changes that suggest we are moving in a post-Christian direction. Roughly summarised, a “post-Christian” context is one in which faith (even Christian faith) is no longer creedal (conceptually) or congregational (sociologically). Our culture is not only increasingly secular and individualist—which a shift toward an “unencumbered self” within an “immanent frame”—but also plural and diverse—requiring that self to engage questions of identity, community, spirituality, and ecology without a conceptual or sociological starting point that is taken as given, unique, and superior.

Here, I want to say that these elements of contemporary culture should not be free from critique and challenge. Nor do I assume that inherited, traditional forms of Christian believing, behaving, and belonging are necessarily false, inauthentic, or alienating. Nevertheless, the wholesale (and retail) rejection of Christian conviction and practice, brought on by shifts in western culture, does raise the humbling question of whether that rejection has merit. And this, in turn, raises the possibility that we might consider adopting a more spiritually positive posture toward these cultural changes.

Some will take such a posture as a “secular sell-out” by people of faith, but I’m not so sure (at least not across the board). Indeed, I think we can restate everything I’ve just said in somewhat familiar theological terms: an alternative posture toward the contemporary world discerns the Spirit of the creator God, who remains the life-giving creator of all that is, doing something good, and right, and beautiful in our cultural changes, there for us to first notice and name, and then engage, embody, and enjoy. Or, put the other way around, a new way of being Christian perceives that these cultural shifts might be the judgment of God on our inherited forms of Christian life and thought, a judgment that can move us toward a change and transformation that might produce more well-being, justice, and integration, not only among our neighbours (“out there”), but also among our Christian households (“in here”).

To put all of this one more way, it seems that we do find ourselves in a new “normal,” a cultural situation in which what is presumed and taken to be “natural” has shifted, both outside and inside the church. It might be that, until recent developments in the west, history and tradition have presupposed a worldview, including an understanding of God, our partnership with God as a people, and our purposes in the world. And this worldview, in turn, largely assumed, a kind of confident sectarianism and parochialism, with clearly defined piety, peoplehood, and prophecy, all rooted in a particular reading of the biblical narrative. But it might be that cultural shifts in identity, community, spirituality, and ecology have eviscerated this parochial confidence. They have, at least, undermined their “naturalness” and “normalness,” making their assumption in Christian conviction and practice more difficult.

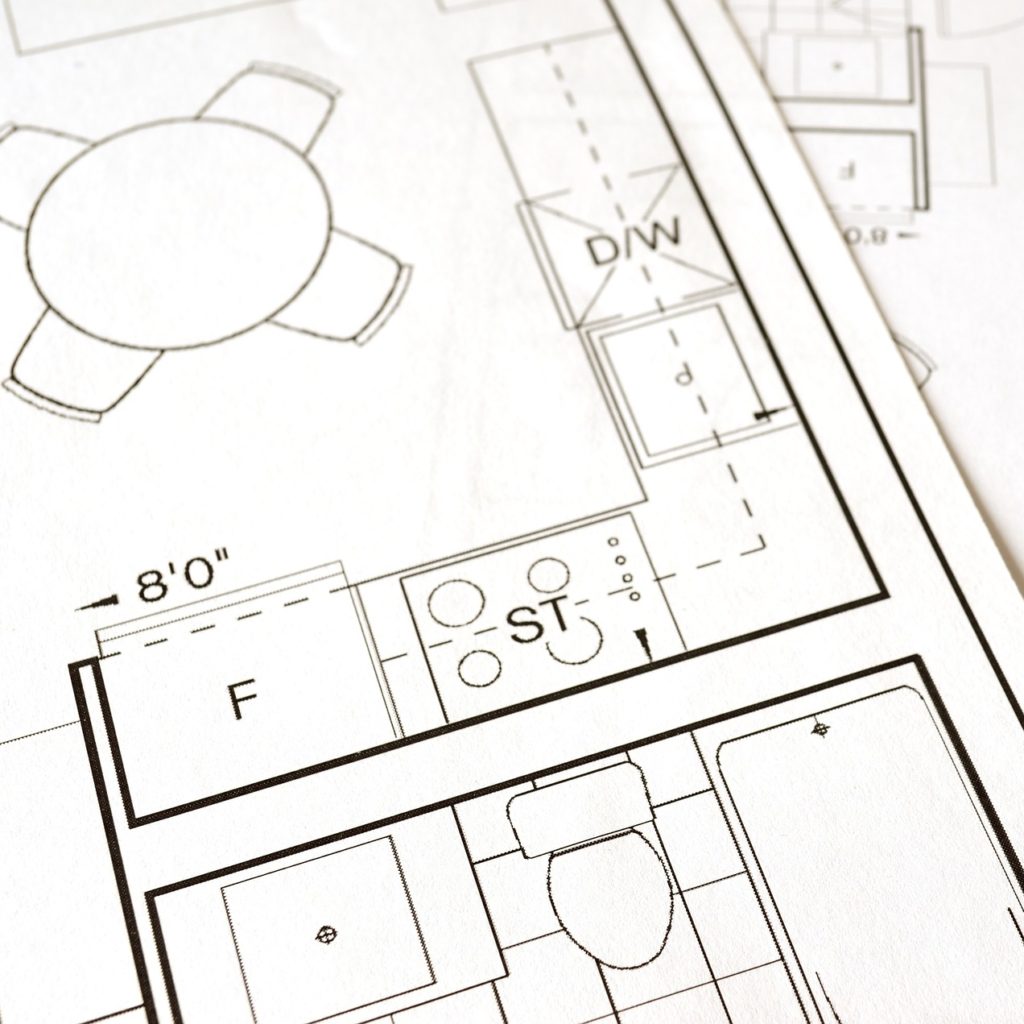

So these observations lead me to the following questions: What if we were to think of our broader cultural shifts in identity and community, ecology and spirituality, as changes in the neighbourhood, or the constituency, or the climate for the Christian houses we wish to build? We will of course still need space for piety, peoplehood, and prophecy, but might we need a new blueprint for making these spaces, in a rapidly changing neighourhood and climate?

As is obvious from these comments, I lean toward an affirmative answer to these questions.

In my next post I say a bit about why.